Tags

19thC, Antonio Canova, Antonio Panizzi, Chiswick, Digamma Cottage, Filippo Ugoni, Giovanni Arrivabene, Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Pecchio, Holland House, John Cam Hobhouse, John Murray, Kensington, Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte, Samuel Rogers, Santorre di Santarosa, Turnham Green, Ugo Foscolo, Ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis, Venice

Ugo Foscolo Cenotaph in Chiswick, London

Here for the first time in my life I have learnt that my name is not entirely unknown among mortals and I find myself accepted as though I were a man who has enjoyed unsullied fame for a century

Ugo Foscolo, writing from London

*************************************************************

The Arrival in London: Holland House in Kensington

When in 1816 one of the Italian servants at Holland House informed Lord Holland that an Italian by the name of Ugo Foscolo had arrived in London, his fame had already preceded him. This celebrated poet and writer, who can be said to have expressed in literature the smoothness and classicism of Canova’s sculptures, was already known in England for his novel Ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis (The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis), published in 1811 by an Italian bookseller and publisher in London. The novel was at first dismissed as a mere imitation of Goethe’s Werther, to which Foscolo had however added a political dimension, which influenced both the Italian Risorgimento and the attitude of the English intellectuals toward Italian unification. Hurling invective against Napoleon, the novel drew the attention of the conservative magazine Quarterly Review, which was at the time competing against the Whig magazine Edinburgh Review. The review of the Ortis by the Quarterly Review was quite flattering, judging the novel as picturesque, anti-tyrannical and in most parts even better than the Goethean model. The reception of Foscolo’s Ortis by “the most wisely crazy people” on earth, his description of the English, made him feel like “a man who has enjoyed unsullied fame for a century”.

John Wykeham Archer, Holland House, Source: Wikipedia

François-Xavier Fabre (1766-1837), Portrait of Ugo Foscolo, 1813, Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale

In spite of the fame that preceded Foscolo’s arrival in “the most Babylonian Babylonia”, as he used to call London, Lady Holland introduced him not only as a famous writer and expert in classical literature, but also as a Milanese exile who left Italy to avoid taking the oath required by the Austrian authority. This alone was enough for him to be considered a libertarian and be welcomed in the Whig milieu at Holland House, even though nobody there seemed to know that his exile was more self-imposed than forced. Also, the Romantic aura that surrounded his arrival coincided with an extremely favourable historical moment (the years after Napoleon’s defeat), which contributed to a renewal of the English interest in Italy. At Holland House Foscolo made acquaintance with such men as John Allen (Lord Holland’s secretary and counsellor), the poet Samuel Rogers, the publisher John Murray (let him reprint the Ortis), Lord Guilford, John Cam Hobhouse, and the antiquary, poet and politician Hudson Gurney, as well as the publishers of the most famous magazines of the time. He was also on friendly terms with the poet and translator William Stewart Rose, a Tory whom Foscolo had already met in Italy and who helped him to move to England.

Part of the gardens at Holland House

Statue of Lord Holland in the gardens

Foscolo as a Jacobin and his Disappointment at the Fall of Venice

Foscolo was born in 1778 in Zakynthos (Zante in Venetian), a Greek island that at the time was a Venetian possession. His family soon moved to Venice in 1788 and he completed his studies at the University of Padua. In spite of considering himself a Jacobin and being against the Venetian oligarchy, after the fall of the Republic the poet developed a negative attitude towards Napoleon, which originated in the cynical way in which the French Emperor treated his homeland, ceding it to Austria with a simple signature in the Treaty of Campoformio (17 October, 1797). Even though disappointed (he had also written an Ode on Napoleon the Liberator), at the beginning of the new century he joined the first Italian army founded by the French, hoping that this would favour a wider movement for the liberation of Italy. But after the Congress of Vienna (1815), which put any hope of independence to an end, he decided to leave his country for good, moving first to Switzerland and then to England. Certainly, at Holland House, nobody would think that, in 1804 and 1805, he had been among the 200,000 soldiers in Saint-Omer, not far from Boulogne-sur-Mer and Calais, ready to invade England to “make them aware of the existence of the Republic” (at the time, the Italian army, or Armée d’Italie, was a mere division of the French army).

Anonymous, Inspecting the Troops at Boulogne, 15 August 1804 (Source: Wikipedia); Foscolo was among the French troops, ready to invade England

His Houses and the Last Years at Digamma Cottage

Upon his arrival in London, Foscolo lodged at the Sablonniere Hotel in Leicester Square, the same hotel that hosted Giuseppe Mazzini 20 years later (see my article on Mazzini here). Around Foscolo many other Italian exiles gathered, and he pleased to consider himself as the primogenito profugo (first-born exile). The Sablonniere was certainly the most humble hotel in the square, and the newly arrived Italians in London used it because it was cheap and managed by an Italian, and therefore one of the few places where they could find Italian food. Between September 1817 and April 1818 he lived at 19 Edwardes Square, Kensington (now an English Heritage site with a blue plaque commemorating his stay), and in June 1818 he rented a cottage at East Moulsey, next to his friend Pamela Fitzgerald’s house, not far from Hobhouse’s cottage in Whitton Park. Later, in 1819, he moved to a small flat over a draper’s shop at 154 New Bond Street. In 1822, after a few years of genteel poverty, in spite of being a regular guest at Holland House, Foscolo became interested in the bungalows and cottages that were being built between Regent’s Park and St. John’s Wood, at a more affordable price than the expensive Regency style buildings of the aristocracy built in other areas. There, he bought two cottages with a 99-year lease and a third one with a 21-year lease. About the same period, he was joined by seventeen-year-old Sophia Saint John Hamilton, whom he used to call at first Mary and then Floriana, an illegitimate child conceived with one of the English girls with whom he had flirted while encamped with the French army near Calais. It seems that it was also thanks to her £5000 dowry, given to Mrs. Hamilton by her grandmother, that Foscolo could buy those properties.

Blue plaque at 19 Edwardes Square

19 Edwardes Square, Kensington

19 Edwardes Square, Kensington

Among the Italians who used to visit him, Giuseppe Pecchio, one of the many refugees who had left Italy after the 1820–21 revolts in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, noted that Foscolo was living with three housemaids, who were actually three young sisters called Marianna, Sofia and Lucy, humorously adding: “He has better taste than Pluto: instead of living with the three Parcae, he lives with the three Graces.” The name of his house in Regent’s Park was Digamma Cottage, as explained by an anonymous writer in the New Monthly Magazine in 1822:

I avoided the way of the lounging places, and strolled thoughtfully on to the Regent’s park [sic], near which I lost myself in a wilderness of cottages and villas, that had sprung up like magic since my last visit to London. One little piece of classic curiosity here struck particularly my attention. It was a brass plate on a door, with the inscription “Digamma Cottage”, which was chosen, I suppose, to puzzle the vulgar; while the ϝ placed above it, though comprehensible to the learned, serves only to announce to the common eye, through its resemblance to one of the characters of our alphabet, the name of the celebrated owner. This information I obtained from a butcher’s boy who was passing, and who assured me that “the ϝ stood for Foscolo, the great Italian poet, and that Digamma was the Latin for Die Game”, which proved, what all the world said, that he was a true patriot into the bargain!

Foscolo said to his English friends that Digamma “is my home, my workshop, my prison and my Champs Elysées.” There were 13 rooms in the house, and as Pecchio noted in another visit in 1823, Foscolo lived “in the lap of luxury, walked on the most beautiful Fiandre carpets, had furniture made of the rarest woods, statues in the hall, a stove filled with exotic flowers and was still served by the three Graces (I think, more expensive than anything else).” Another friend, Scalvini, reported how Foscolo “used to keep gold coins randomly scattered around the room”, and hung lemons and oranges on the trees, to remind him of the Greek climate.

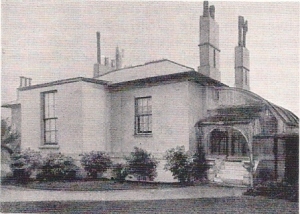

Ugo Foscolo’s residence in South Bank, St John’s Wood (Source: Richard Tames, Political London. A Capital History.)

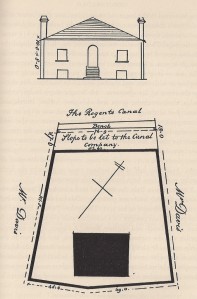

Digamma Cottage’s plant (Source: E.R. Vincent, Ugo Foscolo. An Italian in Regency England.)

The Other Italians at Cappa Cottage and Green Cottage

The other two cottages, Cappa Cottage and Green Cottage, were mainly rented to Italians for £65 a year, which provided Foscolo with the money to cover his expenses. Among them were Filippo Ugoni and Giovanni Arrivabene, both working at Holland House; Giuseppe Pecchio, his future biographer; Santorre di Santarosa, who soon left England for Greece, at the time fighting for independence; the poets Giovanni Berchet and Gabriele Rossetti (Dante Gabriel’s father); and Antonio Panizzi, first Professor of Italian at University College London, and later Keeper of Printed Books at the British Museum and designer of the famous reading room. Some tenants used to meet at Digamma Cottage in the evening, together with the Italophile Lady Hutchinson and other neighbours, to chat and play cards.

According to the people surrounding Foscolo, while living at Digamma Cottage the old Jacobin had become an aristocrat, even though one of his friends, Santorre di Santarosa, said that “if you dig inside, Ugo is still there.”

Isolation and the Sad End in Poverty

While in London, Foscolo criticized the Italians who left Italy to find refuge in England. He found it absurd that during their exile they were always in disagreement about what actions to take against the foreign occupation of the country. He considered their revolutionary actions in Italy “disastrous tragicomedies”; because of this opinion he became isolated from the other exiles. In the last period of his life, Foscolo was arrested for debts, had to get rid of the expensive cottages in Regent’s Park and even sold his books to antiquarian bookshops, being careful not to be taken for a fence. He also changed his name, refused to meet anyone and ended up eating only rice to save money. From the most expensive part of the city he had to move to lower-class areas like Temple and then Somers Town, in a small house called Africa Cottage, with only three rooms and no toilet or running water, which forced him to walk as far as Euston Square to bring water home. He died on 10 September 1827 in Turnham Green, nursed by his daughter and by Miguel Riego, a Spanish priest who took care of his works after his death. The funeral was held on 18 September, when he was buried in the small cemetery in Chiswick, where we can still see his tomb. After the unification of Italy, the ashes were brought to Florence on 7 June 1871 in the Church of Santa Croce, where they remain to this day.

Ugo Foscolo Cenotaph in Chiswick, London

The inscription on the Cenotaph say:

This spot where for forty four years

the relics of

UGO FOSCOLO

reposed in honoured custody

will be for ever held in greateful remembrance

by the Italian nation

Letters from the Exile by Massimo Vangelista is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at byronico.com.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at byronico.com.

Pingback: London and its exiled Londoners | Walking Through London's History 2018

Reblogged this on katalogia.