(The White House Historical Association)

A Trip That Never Happened

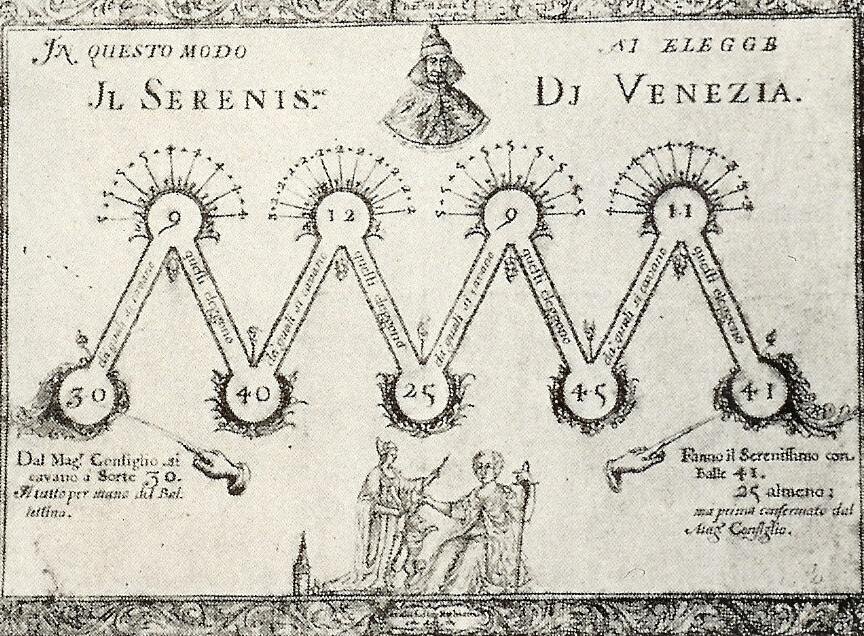

Among some supporters of the old Venetian Republic, there is a myth, one of many circulating on the internet, suggesting that a delegation of American secessionists, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin (referred to as the “Virginians”), visited Venice to study how to govern a republic, with the intention of applying a similar system to the newly established American nation. This intriguing tale highlights the enduring fascination with historical republics and their potential influence on the formation of the United States.

(from The Ballot Boy)

While Thomas Jefferson had a profound appreciation for antiquities and the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio, there is no concrete evidence to support his visit to the Veneto region, including Venice. In fact, historical records indicate that Jefferson’s travels in Europe, which began in the south of France, did not take him as far north as the Veneto.

Jefferson’s documented travels show that the closest he came to the borders of the Venetian Republic was Milan, Italy. However, due to time constraints and his extensive European journey, he did not venture further into the Veneto region. This itinerary provides strong evidence that Thomas Jefferson did not visit the Veneto or Venice during his travels.

Thomas Jefferson’s European Journey Post-American Revolution

It is established that between March and June 1787, Jefferson spent time in Italy, marking the only confirmed record of his presence in the country. Let’s delve into the specifics of his activities during this period, commencing with his keen interest in classical architecture (you can readily access Thomas Jefferson’s European travel itinerary following the American Revolution by visiting the Library of Congress website; see the bibliography below).

Jefferson Was Interested In Classical Architecture, Not In Its Reinterpretations

In the words of Robert Tavernor in Palladio and Palladianism, “Jefferson sought enlightenment in the pristine sanctity of antiquity and republicanism. There were few positive lessons that contemporary Europe could teach America. He admired France for her buildings, but he complained that architecture in England was ‘in the most wretched style I ever saw‘.” According to Tavernor, this perspective helps explain his lack of motivation to explore the works of Andrea Palladio during his time in northern Italy. Instead, he chose to collect grains of Italian rice to sow upon his return to America.

Jefferson found his true inspiration in the remnants of ancient structures. During his visit to Nimes in southern France, he was captivated for “whole hours… like a lover at his mistress” by the Roman temple known as the Maison Carrée. His admiration for this ancient masterpiece endured through drawings published by Charles-Louis Clérisseau in his Antiquités de France, Monuments de Nîmes in 1778.

In a parallel with Inigo Jones, who also devoted substantial time to studying ancient Roman architecture during his Italian sojourn, Jefferson’s fascination lay in the fundamental principles that underpinned classical architecture, rather than contemporary reinterpretations of classical precedents.

So, although Jefferson’s primary focus was on classical architecture, and this might have led him to the land of Palladio, he chose not to make the additional journey to the Veneto.

Jefferson’s Italian Journey: The Itinerary

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson embarked on his journey through Northern Italy. He left his carriage in Nice and continued his travels on mule-back, crossing the Alps on his way to Turin. Along the way, he passed through Scarena, Sospello, Breglio, Saorgio, Fontan, Ciandola, Tende, Limone, Cuneo, Centallo, Savigliano, Racconigi, and Piorino.

While passing through Breglio, he was captivated by a breathtaking view of Chateau di Saorgio, where he noted that “the castle and village seem hanging to a cloud in front.” This view left a profound impression on him, and he even advised fellow countrymen to revere it:

fall down and worship the site of the Chateau di Saorgio, you never saw, nor will ever see, such another. This road is probably the greatest work of the kind which ever was executed either in ancient or modern times. It did not cost as much as one year’s war.

Other places along the route, such as Ciandola and Tende, did not leave a significant impression on him: “Ciandola consistes of only two houses, both taverns. Tende is a very inconsiderable village.”

Jefferson arrived in Turin on April 16, 1787, and then proceeded through Settimo, Chivasso, Ciliano, and San Germano to Vercelli. On his way to Milan, he passed through Novara, Buffalora, and Sedriano, where he observed the rice husking process. On April 20, he finally reached Milan and was hosted by Count Dal Verme, who directed his attention to the most noteworthy objects since Jefferson had limited time to spend in the city.

In a letter to George Wythe, a lover of classical knowledge, Jefferson wrote:

In the latter country my time allowed me to go no further than Turin, Milan, and Genoa; consequently I scarcely got into classical ground. I took with me some of the writings in which endeavors have been made to investigate the passage of Annibal over the Alps, and was just able to satisfy myself, from a view of the country, that the descriptions given of his march are not sufficiently particular to enable us at this day even to guess at his tract across the Alps. In architecture, painting, sculpture, I found much amusement; but more than all in their agriculture, many objects of which might be adopted with us to great advantage. I am persuaded there are many parts of our lower country where the olive tree might be raised, which is assuredly the richest gift of heaven. I can scarcely except bread. I see this tree supporting thousands in among the Alps where there is not soil enough to make bread for a single family. The caper too might be cultivated with us. The fig we do raise. I do not speak of the vine, because it is the parent of misery. Those who cultivate it are always poor, and he who would employ himself with us in the culture of corn, cotton &c. can procure in exchange for that much more wine, and better than he could raise by it’s direct culture.

Leaving Milan on April 23, Jefferson arrived in Pavia the same day and reached Genoa on April 25. Two years later, he recommended William Short to stay at the Hotel du Cerf in Genoa: “for pleasantness and convenience, if you take a room looking to the sea.” After exploring the suburbs of Genoa, he sailed on April 28, enduring seasickness for two days. As he strolled along the Italian Riviera from Luana to Albenga, he marveled at the region’s beauty and tranquility, suggesting it as an ideal place for those seeking seclusion amid nature’s bounty:

If any person wished to retire from his acquaintances, to live absolutely unknown, and yet in the midst of physical enjoyments, it should be in some of the little villages of this coast, where air, water and earth concur to offer what each has most precious.

At Albenga, he encountered the poorest hotel accommodations of his travels, a matter he would later complain about in his letters. Despite this, he continued his journey by mule: “the wind continuing contrary, I took mules at Albenga for Oneglia.” From there, he paid the felucca captain and took mules to Nice, arriving on May 1, and three days later, on May 4, he finally reached Marseilles.

Bibliography

Adams, William Howard, “The Virginians and the Veneto”, The Virginia Quarterly Review, vol. 63, no. 4, 1987, pp. 646–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26437904. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Dumbauld, Edward H., Thomas Jefferson, American Tourist: Being an Account of His Journeys in the United States of America, England, France, Italy, the Low Countries, University of Oklahoma Press, 1976

Forster, Kurt W., “Viaggi in terra palladiana”, in Palladio nel Nord Europa. Libri, viaggiatori, architetti, Skira, 1999

Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Papers – https://www.loc.gov/collections/thomas-jefferson-papers/articles-and-essays/the-thomas-jefferson-papers-timeline-1743-to-1827/1784-to-1789/

Tavernor, Robert, Palladio and Palladianism, Thames & Hudson, 1991

***************************************************************************************************************

Letters from the Exile by Massimo Vangelista is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at byronico.com.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at byronico.com.